Kate Davies, a member of the Society, ran a Margery Allingham focused knitting and book club in summer 2024. This has been followed by the publication of the essays in ‘Margery Allingham’s Mysterious Knits.’

Contributors include Kate, Tom Barr, Caroline Crampton, Veronica Horwell, Julia Jones, Sarah Mackay and Imogen Robertson. The essays explore themes that illuminate Margery Allingham’s creative world: from the relationship between patterns and plotting, to the fashion, film and popular culture of the 1930s and 1940s; from the wide ranging role played by knitting and knitters in detective fiction, to the distinctive Essex landscape that inspired Margery Allingham throughout her life.

Here is Kate’s essay, ‘Up Apron Street.’

Caution: my essay discusses More Work for the Undertaker, though without crucial plot points or spoilers. That said, you may wish to finish the novel before reading what follows!

As a mystery novel, More Work for the Undertaker has an interesting beginning. Albert Campion turns down the role of colonial governor in order to investigate the Palinode case. He doesn’t take all that much persuading, and indeed seems not only happy but also weirdly relieved to be able to exchange exotic climes and imperial prestige for the shabby environs of Apron Street, with its shops and pubs and “practical” undertaking. Together again with Lugg, amid the crumbling buildings of Bayswater and Paddington, an area of London that, as Charlie Luke puts it, has “gone down like a drunk in the last thirty years”, Campion is quickly in his element.

Frontispiece map from More Work for the Undertaker (1948)

He is drawn to the colourful rhythms and characters of Luke’s “manor” as much as the charismatic DDI (Detective Divisional Inspector) himself, and positively relishes the opportunity to sojourn among the rag-tag crew of stout- and Sleep-Rite-quaffing misfits who inhabit Renée Roper’s boarding house.

The London boarding house provides a very promising setting for a crime novel. Within its walls, groups of complete strangers live in a curious forced intimacy, sharing their bathrooms, food and personal habits while struggling to get by, and paying rent. In such single-occupancy spaces, privacy is oddly permeable as disparate lives and ways of living rub up against each other in the kitchen, dining room or hallway.

Petty resentments and suspicions abound. Who is that new chap on the third floor? Can the occupant of room 11 really be trusted? What does she do all day? Through all the queuing for the bath, odd odours drifting from the basement and quiet footsteps on the staircase in the early hours, unassuming neighbours might not quite be what they seem, and any pleasant face might hide a dark past full of hidden secrets.

Given that the boarding house offers such fertile fictional terrain, it’s interesting to note that, among British writers of detective fiction’s Golden Age, Margery Allingham is one of only a handful to properly explore it. While Agatha Christie situates several sparkling plots in seaside hotels, and a London boarding house has a small role to play in Josephine Tey’s The Man in the Queue (1929), Mavis Doriel Hay is perhaps the only other of Allingham’s golden-age contemporaries to make the London boarding house the heart of a brilliant mystery, in her Murder Underground (1934).

“As rich as a dark plum cake”

If Coroner’s Pidgin is an uncomfortable novel of the pre-post-war transition, in More Work for the Undertaker (1948) Allingham has most definitely moved on from both the Golden Age and the war to a completely different time and place. It’s an exceptionally confident book, “a slice of London as rich as a dark plum cake” in Elizabeth Bowen’s words, brim-full of humour, and animated with the electric energy of the very appealing Charlie Luke. Often described as Dickensian in its colourful urban atmosphere, More Work for the Undertaker might fruitfully be read alongside two other contemporary British novels (arbitrary classified as “literary” rather than “genre” fiction) which are also set in boarding houses: Norman Collins’ London Belongs to Me (1945) and Patrick Hamilton’s Slaves of Solitude (1947), though Allingham’s novel has far less 1930s-focused nostalgia than the former, and, unlike Hamilton’s fine book, the world that it depicts is very definitively post-war.

Rather than replaying the familiar conventions of the 1930s British murder mystery, with its country houses and moneyed elites, in her sideways move to Apron Street, Allingham seems instead to take a pleasurable detour into the bombed-out, fast-paced, can-do narrative world of Ealing Comedy.

In her later novels, she was to provide a much darker perspective on crime and criminality in post-war London, but in More Work for the Undertaker, both serial murder and lowbrow malfeasance are equally laughed off with the same “essential lightness and optimism” that Michael Newton describes as the hallmark of Ealing’s great 1950s films. And just like those films, too, Margery Allingham’s book is very definitely about post-war Britain.

Both Allingham and Ealing provide particularly vivid snapshots of the British mid-century socio-cultural landscape, and it is definitely no mysterious coincidence that the dubious goings-on of The Lavender Hill Mob (1951) and The Ladykillers (1955) also take place in London boarding houses. For, by the turn of the 1950s, these spaces of single-occupancy urban living were recognisably potent symbols of the present state of the nation. Why might this be the case?

Boarding-house Britain

In the immediate post-war years, Britain struggled with an acute housing crisis. During the war, new houses were not built and the condition of existing stock deteriorated, while over half a million homes were ruined or rendered uninhabitable by falling bombs. Demand for decent housing far exceeded its supply, and in 1946, 40,000 young people took matters into their own hands by creating their own ad-hoc homes in disused military encampments.

Though the post-war squatters’ movement was not well organised and somewhat short-lived, it certainly cast a spotlight on the profound effects of years of war on Britain’s domestic landscape. The nation now undergoing rapid demographic change, due to necessary inward immigration and the post-war baby boom, was also one in which the private spaces of the bourgeois family home had become an apparently unachievable ideal.

In the same year as frustrated families began squatting in former army quarters, 1,500,000 people moved to London. And, in the main, the city’s new inhabitants were not families but single individuals. Where were they all to live? A thousand bombs had fallen on the area of London in which Margery Allingham liked to set her novels, and whole streets had been destroyed.

Even before the development of new social housing projects (which provide the setting for the first death in The China Governess (1963)), the character of Margery Allingham’s old Bayswater stomping grounds had undergone a rapid change. Elegant town houses, once the private homes of prominent wealthy families, had been divided into bedsits, while formerly graceful—now decaying—mansions carried signs advertising rooms to let.

Such rooms were occupied by diverse people of all ages, all of whom were finding their feet and rebuilding their new lives in the same make-do world of utility clothes and rationed bread. Stereotypes like the formerly genteel, now down-at-heel elderly resident, or the unfeasibly wealthy landlady, rapidly became the stock-in-trade of British satirists, while the drab cabbage-scented rhythms of daily life in the boarding house and bedsit-land of Bayswater and Paddington were immortalised in books such as Winifred Ellis’ London—So Help Me! (1952), which was evocatively illustrated by Ronald Searle.

Making do and making up

London’s new single-occupancy landscape was also intriguingly represented in the Britain Can Make It exhibition held in 1946 in the Victoria and Albert Museum, at which large crowds queued day after day to view the “furnished rooms”. Designers imagined the ideal tenants of modern single-occupancy dwellings—nurses, civil servants, navvies, BBC radio sports commentators—and created interior decor schemes specifically for their social class, assumed aesthetic preferences and leisure activities, from phonographs to knitting.

But while Britain Can Make It elevated mid-century modern single life into an idealised abstraction, in reality the landscape of the post-war bedsit and boarding house was one of threadbare domesticity, economic precarity and a population of itinerant, marginal characters who, if they were not engaging in activities then deemed criminal, might certainly exist somewhere on the borders of respectability. “Just as the edges of Bayswater had frayed into slums,” memoirist and novelist William Plomer recalled of the neighbourhood in which he sat down to write Museum Pieces (1952), “so the population had a grubby fringe, or rather a fluid margin, in which sank or swam the small-time spiv, the deserter, the failed commercial artist turned receiver, the tubercular middle-aged harlot, the lost homosexual or the sex maniac.”

Such colourful neighbourhood characters also feature in Janson Woodall’s much more recent (and utterly delightful) illustrated memoir of his childhood growing up in a post-war Paddington boarding house, 4 Sussex Place (2023), in which tenants inexpertly perform odd jobs in lieu of rent, conduct a variety of more or less legitimate small businesses, share dirty jokes together in the kitchen, and discover unknown corpses in the bedrooms.

In autobiographical texts like those of Plomer, Woodall or Ellis, the boarding house emerges as a fascinatingly idiosyncratic shared domestic space. It’s a place of proximity and estrangement, of transgression and permission, a place in which unorthodox identities and wayward behaviours are rented rooms in which to flourish. Time and again, post-war boarding-house memoirs and fictional narratives suggest how, when living under the same roof, people have to learn to get along, and become enduringly tolerant of each other’s differences, regardless of age, cultural background or social origin.

Ad-hoc friendships and makeshift families eventually form from all these lost souls thrown together, and the very provisionality of boarding-house living seems itself to enable a curious jouissance and love of life.

Before the war, boarding houses were often represented as spaces of dreary and depressing giving up, but it is interesting that, by the later 1940s and early 1950s, representations of their hybrid model of single-yet-somehow-communal dwelling tend inevitably towards the comedic and light-hearted. In post-war British culture, the boarding house is not simply a place of making do, or making the best of it, but a place of creative making up: an imaginative place of possibilities, in which anything could happen.

At Portminster Lodge

All of these elements are at play in Allingham’s More Work for the Undertaker, in which, shabby exterior and visible decline notwithstanding, Portminster Lodge bristles with the palpable vitality and mother-hen generosity of its landlady, Renée Roper. Misunderstandings and small jealousies are rife, yet everyone supports each other kindly, beyond their obvious differences (and the suspicion of possibly murderous intent). Individual eccentricities flourish in the name of getting by, the hours are very irregular, and privacy seems completely porous: Renée might turn up at your bedside at any moment in her frilly happy coat with a dram of whisky, and before you know where you are, another resident has hesitantly knocked and come in to join the party.

Much of the delicious humour of More Work for the Undertaker arises from the everyday proximities of the boarding house, which grant the reader unusual insight into the personal habits and corporeal needs of the residents of Portminster Lodge. Lawrence Palinode’s suspected adenoidal problems are confirmed by the volume of his midnight snores, while Miss Evadne is an amalgam of her room’s sticky surfaces and heavy fabrics, its chilblain preparations and powdered egg. Much of Campion’s investigative work, meanwhile, takes place not just from the intimate spaces of his bedroom, but between the sheets of his bed.

Generally speaking, Albert Campion is not much of a physical presence, yet in More Work for the Undertaker, the reader feels the bodily sensations of the lean detective very palpably. During an extended night-time sequence in which Campion wanders around Portminster Lodge clad only in a dressing gown, we experience with him the tortuous rim of the upturned metal bucket on which he is forced to sit during his first meeting with Miss Jessica, and through the wily words of Jas Bowels we are called upon to briefly imagine the silhouetted vision of his naked form against the backdrop of an open window.

In Portminster Lodge, old age is welcomed alongside youth. An octogenarian char thrives on physical labour as much as neighbourhood gossip, while a teenage girl discovers her own style and sexuality. Everyone (with the exception of Lawrence) turns an understanding blind eye to Clytie’s midnight escapades, while Bowels and Son’s highly suspect activities are tolerated in the basement. And if Portminster Lodge is a permissive place, enabling the pursuit of individual eccentricities and curious (potentially criminal) practices, then it’s a space for the transformation of identity as well.

Cajoled into fixing Miss Evadne’s electric kettle, flattered into the belief that he might be mistaken for a Shakesperean actor, Sir William Glossop leaves Portminster Lodge a slightly different, slightly more colourful person than the tight-lipped civil servant who went in.

Figures of resilience

The same cheek-by-jowl backdrop of harmless eccentricity and small-time criminality, together with a similar atmosphere of creative potential and identity transformation, pervades the boarding house of Tibbie Clarke’s and Charles Crichton’s The Lavender Hill Mob (1951). In this brilliant crime caper, a not-so-prim elderly landlady relishes the hard-boiled details of American detective fiction (but never pauses from her knitting), while her chief boarder, the apparently completely unassuming and respectable bank clerk Henry Holland (Alec Guinness), successfully plots and executes an ingenious bullion robbery with the help of fellow tenant Alfred Pendlebury (Stanley Holloway) and their “mob” of two-bit London crooks.

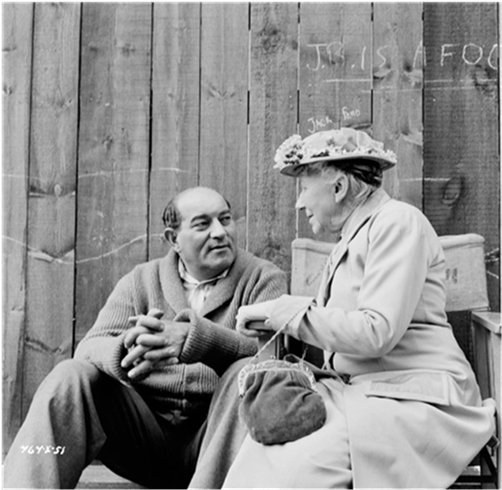

Danny Green (“One round”) and Katie Johnson. One round has the physical presence I imagine for Lugg, if not his character

Renaming himself “Dutch”, Holland assumes not just a street moniker but a new carefree identity, and, through the transformative spaces of Lavender Hill, rejects the tedium of his working life by taking a chance on affectionate friendship, creative possibility and laughter.

Productive comparisons might also be drawn between More Work for the Undertaker and The Ladykillers, in which a criminal plot is hatched in north London rented rooms under the mild eye and gentle ministrations of unwitting landlady Mrs Wilberforce.

Like the Palinode siblings, Mrs Wilberforce is an Edwardian relic whose decaying gentility seems completely out of step with the brash, grasping individuality of the modern streets around her. And like Jessica Palinode, too, she’s a figure of curious resilience, whose gifts of openness, resourcefulness and unstinting compassion grant her a kind of moral licence to survive (and thrive).

While Miss Jessica dedicates her meagre rations to support those suffering in post-war Germany, Mrs Wilberforce brings her neighbourhood to a standstill to intervene in a scene of animal cruelty. Against her unshakeable standard of basic goodness, the forces of contemporary violence, greed and fraud all fall.

In a lecture given in later life, the director of The Ladykillers, Alexander Mackendrick, spoke of how the elemental moral battle of the boarding house might be read as a post-war state-of-the-nation fable.

After the war, the country was going through a kind of quiet, typically British, but nevertheless historically fundamental revolution. Though few people were prepared to face up to it, the great days of the empire were gone forever. British society was shattered with the same kind of conflicts appearing in many other countries: an impoverished and disillusioned upper class, a brutalised working class, juvenile delinquency … and the collapse of “intellectual” leadership. All of this threatened the stability of the national character.

More Work for the Undertaker occupies this quintessentially British cultural moment very precisely—and, just like Mackendrick, Margery Allingham’s creative instinct was to try to represent it with an affectionate light touch, buoyant good humour, and a few deaths thrown in. Campion is offered a walk-on part in the last days of the empire, but he obviously much prefers the role of star boarder in Bayswater’s shattered single-occupancy streets. And surely the reader prefers this too, as we laugh in the face of the nation’s uncertain future through the broken bottles and paper bags that blow around the corner of the Harrow Road, through the weeds that Miss Jessica gathers in Hyde Park.

Apron Street might well be street slang for the undertaker’s work, but here in this ramshackle manor, life continues to flourish through the expansive good nature and tolerance of Renée Roper and in the unfailing warmth and optimism of Charlie Luke.

“What ho! Coffins at eight!”

Margery Allingham’s Mysterious Knits

UK rrp: £25

ISBN 978-1-7396582-6-7

available here: https://www.shopkdd.com/books