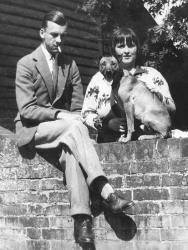

Philip Youngman Carter (“Pip”) at his desk

(© The Margery Allingham Society)

Youngman Carter’s contribution to crime fiction was fourfold. He was associated with his wife, Margery Allingham, in the planning of many of her books, particularly those she wrote between the wars; he designed the wrappers for most of his wife’s books and for works by other eminent crime writers, such as Carter Dickson, Georges Simenon, Gladys Mitchell, Leo Bruce and Henry Wade; he wrote more than thirty short crime stories remarkable both for meticulous logic and freewheeling fancy; and, after his wife’s death, he completed her last novel and produced two poised and idiomatic sequels.

Philip Youngman Carter was born in Watford, to the north-west of London, on 26 September 1904, the only son and elder child of Robert and Lillian Carter. His father, the local headmaster, died suddenly in April 1914, when his son was only nine. Two years later, the boy won a scholarship to the famous Bluecoat School, Christ’s Hospital, near Horsham, which proved a major influence in the shaping of his life. He became one of the school’s most loyal and devoted sons, and to the end of his life Christ’s Hospital and those associated with it were of first importance to him.

In 1921 he moved on to study art at the Regent Street Polytechnic in London. While still a student he began to make his way as an artist, producing drawings for The Daily Herald, through the good offices of his former English master, R.C.Woodthorpe. He also designed the first of over 2000 book wrappers and even, as his autobiography makes clear, the occasional vulgar postcard.

He was seventeen when he met Margery Allingham, his future wife, having got in touch with her family in the belief that they were cousins of his own (though , in fact, they were not related). They worked together on the production of her play about Dido and Aeneas, for which he designed the settings, and, at her insistence, he provided the wrapper for her first novel, Blackkerchief Dick, published in 1923.

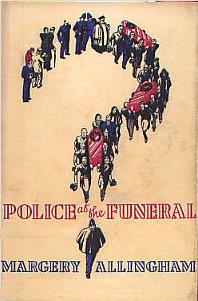

They were married in 1927, living at first in London, but moving to the Essex countryside within a few years, when circumstances allowed. From 1935 to their deaths their home was D’Arcy House, the handsome Georgian house at the heart of the Essex village of Tolleshunt d’Arcy. While his wife was establishing herself as a novelist, Youngman Carter became a prolific graphic artist, distinguished particularly in the undervalued field of dustwrapper design for books. His designs enhanced the work of many of the most celebrated writers of the day: H.G.Wells, G.K.Chesterton, Eden Phillpotts, Margaret Kennedy, Daphne du Maurier, Rebecca West, John Steinbeck, J.B.Priestley, Georgette Heyer and Graham Greene. Invariably he contrived to serve the text while making an impact of his own. He was always stylish and confident, and his work remains fresh and appealing long after many of the books that inspired it are forgotten. He was not above using a good idea twice, so that his device for The Mind Readers echoes that for Police at the Funeral, and the elegant mask motif of a novel by Rebecca West recurs to brilliant effect on The Beckoning Lady.

Police at the Funeral dustjacket

by Philip Youngman Carter

By 1940, after some delays because of his age, he had secured a commission with the R.A.S.C., and he subsequently saw service in the Western Desert and the Middle East. His account of the fall of Tobruk is one of the most vivid passages in his autobiography. Later he became Editor-in chief of army publications in Persia and Iraq, co-founding and editing the official army magazine ‘Soldier’. In Baghdad in 1943 he drew a portrait of the boy King Feisal of Iraq.

He was demobilised in 1946 with the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel, and continued to work as a journalist in civilian life. After a brief spell as Features Editor for ‘The Daily Express’, he joined ‘The Tatler’ in 1947 as Assistant Editor. He contributed portraits and theatre reviews and wrote lighter pieces under the pseudonym ‘George Gulley’. Later he took over as Editor, making the glossy society magazine, in Jack Morpurgo’s words, ‘too good for its conventional readership’. From its inception in the early fifties he was also associated with ‘The Compleat Imbiber’, the house magazine of Gilbey’s, the wine and spirit merchants. Here again, both in his editorial role and his occasional contributions, he used the ‘Gulley’ by-line. During the post-war years he maintained a London flat in the former home of George du Maurier, near the British Museum.

In 1957 he left Fleet Street to resume his career as an artist and to expand his activities as a writer. He wrote and illustrated a travel book, On to Andorra, and a series of books on wines and spirits, published as a sequence called ‘Drinking for Pleasure’. He continued to design dustwrappers, including a long series for Simenon, and in the early sixties produced paperback covers for several of Dorothy L. Sayers’ Wimsey novels. He wrote over forty short stories, the majority criminous, with a smaller group on military themes. ‘Argosy’ and ‘EQMM’ were principal outlets for his shorter fiction. He also illustrated the reissue of The Oaken Heart, his wife’s war-time autobiography.

On the premature death of his wife in 1966, he completed her last novel, Cargo of Eagles, so effectively that the join is probably not apparent to most readers (though Edmund Crispin claimed to be able to see it). His intention to keep Albert Campion alive through a series of novels was cut short by his death after two only had been achieved: Mr Campion’s Farthing and Mr Campion’s Falcon (Mr Campion’s Quarry in the U.S.). He died on 30 November 1969, after an operation for lung cancer.

The main source for a view of Youngman Carter’s personality is his autobiography, All I Did Was This, published posthumously in 1982 in a limited edition. He writes with impressive recall of his early life and admits that much of his character and outlook was determined in his boyhood. Throughout his life he appears to have divided his fellows into ‘good chaps and stinkerinos’, and how one regarded him must clearly depended on how one was regarded by him. He is variously described as cynical and sardonic, forthright and formidable, and ‘appallingly selfish’. He had ‘uninhibited prejudices’ in which he delighted, ‘a bee in his bonnet about trespassers’ and a boyish relish for ‘private games’, often at the expense of others. To those who incurred ‘the full and scabrous vigour of his distaste’ he was an implacable and ‘vitriolic’ enemy.

He was nonetheless a gregarious and convivial man, who disliked solitude and greatly enjoyed entertaining his friends and associates. His wife described him as ‘one of the most hospitable people on earth’, and the parties they gave became legendary in their circle (so much so that Joyce Allingham, in editing the autobiography , felt that ‘No account of Pip would be complete that did not give some description of one of these events’). He was ‘a fine friend’, greatly supportive of those who won his regard and unfailingly loyal to them. Loyalty was, for him, ‘the indispensable quality’, especially so in his dealings with Christ’s Hospital and its sons. He valued enormously his membership of the Amicable Society of Blues, the exclusive old boys’ association; and he worked with Edmund Blunden, Eric Bennett and Jack Morpurgo on The Christ’s Hospital Book, published in 1953, contributing a memoir of his time at the school and drawings of three major figures in its history.

He was a keen cricketer, prominent in local games and active as a Lord’s Taverner on more ambitious occasions. For some years he umpired the annual match between authors and publishers. He loved the theatre and describes his youthful experience of London’s theatrical world with vivid affection in his autobiography. He wrote dramatic criticism for ‘The Tatler’ and was elected to the Garrick Club, where, in distinguished company, his portrait of Martita Hunt now hangs.

He was clearly an unusually gifted man, brimming with creative vigour and with a multiplicity of talents and enthusiasms always on tap. Much of his surplus energy went into inventive projects of various kinds – games and competitions, ideas for journals and outlines for television. His wife recorded his ‘perpetual interestedness’ and attributed to him ‘two thirds of the ideas and half the jokes’ in her early novels. Even within his major fields of activity he was versatile – not only a designer but an illustrator and portraitist, not just a novelist but a travel-writer and drama critic. Despite the range of his gifts and the distinction of his achievement, those close to him suggest that he might have found a wider fame if his father had lived to oversee his son’s career, or if he had been less diffuse, more concentrated in his endeavours. Joyce Allingham sees the loss of his father as some explanation of ‘the mystery that he who wrought so hard and achieved so much did not achieve all of the success and fame that his skills and dedication merited’; and Jack Morpurgo records as fact that ‘he suffered inevitably but erroneously from the slur of slightness’, and was unfairly ‘pitied and patronised…for living out his professional life in the shadow of his undeniably famous wife’. In retrospect, it is cause for regret that so much of his creative energy went into dustwrappers, since so few have survived to contribute to his posthumous reputation. However good they are, they have no real currency and largely blush unseen. His drawings, too, are less well-known than they deserve to be: no published collection exists and there has been no exhibition to boost his celebrity. Even his ambition to establish his own Albert Campion series was thwarted by his death just as he was hitting his stride.

The two novels he had time to write are as elegant and finished as anything in his oeuvre. Death by violence is common to both but in neither is the whodunit element of central importance. Rather, they are mysteries, stylish, shapely and entrancingly tricky. They inhabit a well-favoured world with echoes of Allingham: Guffy Randall reminiscences at his London club and a minor villain left Totham under a cloud. The ambience is worldly and the trappings are superior; and the narratives are distinguished by mischievous wit and a style at once precise and decorative. The author’s eye for social nuance is everywhere apparent; so, too, is his ease of contrivance. In each book a precious secret is obsessively sought by an unscrupulous man in command of disruptive forces: a formula in the one, a latitude in the other. The predators are properly routed by Mr Campion, whose adroit manipulation of people and events effects in each case a gratifying climax. He collaborates on both investigations with ‘Elsie’ Corkran, the former Security chief from The Mind Readers and Cargo of Eagles.

Mr Campion’s Farthing charts the progress of an elusive Russian scientist, who is up to something and must be found (and whose name, Kopeck, gives the book its title). It also elaborates an ambitious programme of persecution against a brave old lady, whose home, Inglewood Turrets, is a late-Victorian survival adapting to the present as a cultural centre. The search for Kopeck begins at the Turrets, so that the owner is doubly harried: by those who want the scientist’s secret and by those who wish to buy – and drive – her out. Attempting to serve both masters is a treacherous private eye, whose Achilles heel is a craving for forged stamps. Much of the pleasure of the novel derives from the buoyant account of the ménage at the Turrets, which offers ‘a vision of literary and artistic England as it was seventy-odd years ago’. The author achieves a profusion of meticulous detail, giving character to interchangeable landscapes by Farquharson and Yeend King, and inventing three volumes of ‘forgotten memoirs’ in which the house featured. In his study, the master’s portrait is particularised as ‘the Solomon version of 1898’; and the Watts removed from the dining-room is a ‘woolly’ allegory entitled ‘Myopia with Ennui’. The hostess is a game old girl in the grand Allingham tradition, with a riveting line in cultural small-talk; and the new butler is none other than Campion’s son Rupert, now a drama student, the bright chestnut hair inherited from his mother a principal clue to his identity. On one occasion the guests include a woman who breeds schipperkes, on another, a couple named Croesus, who are ‘as poor as church mice’.

In the second novel, the falcon, like the farthing, is human, and independent young woman called Anthea Peregrine – or ‘Little Miss Knowall’ to the local superintendent. Again like Kopeck, she has a habit of disappearing, from a luxury hotel in the Cotswolds with half-tester beds and a pretentious menu, and from the Brett School on the Suffolk coast, where a Roman ship is being excavated. A death at the hotel prompts considerable interest in the dead man’s estate, by an obese asthmatic, and by the hotel manager, whose own death, at Brett, is a sequel. Campion’s quest for a vanished geologist, of whom no photograph seems to exist, ramifies into an intricate problem of identity, ravelled and unravelled by a masterly hand.

The author’s eye for detail is unfailingly alert: for the prototype cheque at Saffron’s Bank; for the ‘quilted upholstery’ of an expensive London pub; for the balcony at Guido’s from which ‘one can see all the other tables’; and for the opening verses of a phallic song, commemorating the fall of the Stone of Burdon. A phone call from Amanda, selling planes in Washington, reminds us of her vocation and her voice. It also evokes the whole line of novels from Sweet Danger, and highlights what we lost by Youngman Carter’s death.