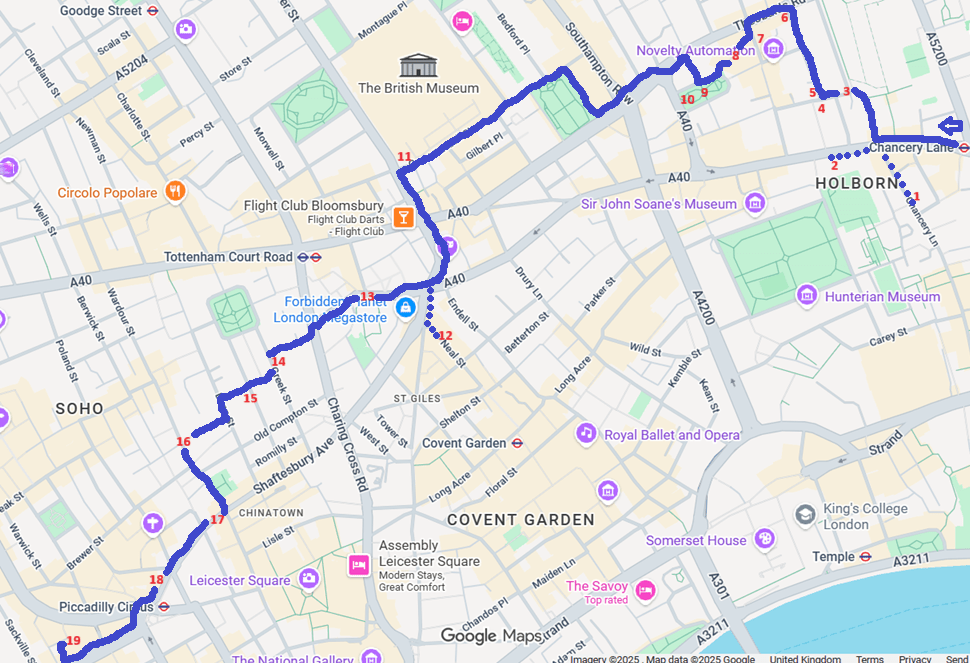

This walk explores sites related to Margery and her novels and short stories taking in a) real places relevant to her life e.g. homes where she lived with Pip and the church where they were married, b) real places which she used (sometimes under thinly disguised pseudonyms) in her fiction, and c) places which correspond to details of locations appearing in her fiction sufficiently to suggest they were the places Margery had in mind when writing the relevant passages.

Numbers given in (Bold) in the text correspond to the red numbered locations on the map of the route. The walk should take no more than 1 ¾ hours to complete at a relaxed pace.

We are greatly indebted to B. J. Rahn for her researches upon which we have drawn heavily in preparing this walk.

Start from Chancery Lane tube station. Leave via Exit 1 (Gray’s Inn Road). Walk west along Holborn until you reach the narrow entrance to Warwick Court on your right.

On the other side of the street is Chancery Lane. You may take a short diversion here (take care crossing the busy road) along Chancery Lane (1). There is a brief mention in Look To The Lady of a safe deposit located on Chancery Lane but no clues to identify any location more accurately.

Before turning into Warwick Court, you can look further west along Holborn towards the line of office blocks on the opposite side of the road (2). This is the site of the flat on Middle Row Place which was Margery and Pip’s first married home, where they lived from 1927 to 1931. The flat provided the location for two short stories: The Border Line Case and The Lieabout. The block has been long since demolished and the faceless offices built in its place.

Turn right into Warwick Court (except if you are following the walk at the weekend when the route through to Jockey’s Fields is closed and the gateway locked) and walk to the end. Continue ahead and when you reach an open space ahead and to your right, take the small gateway on your left, up steps and through the enclosing wall, to reach Jockey’s Fields (3). The Museum of Wine in Coroner’s Pidgin is described as occupying a “little house” in this street.

The alternative route to reach Jockey’s Fields at the weekend is to continue some 50 metres further along Holborn and take the right turn down Brownlow Street. At the end of Brownlow Street you turn right and reach point (3) at the end of Jockey’s Fields in less than 20 metres where you will see the gate (locked at weekends) through which you would have emerged had you been able to follow the intended route.

Continue ahead a few metres along Sandland Street to reach the turning into Bedford Row on your right (4). This junction and the buildings on it (including what is now the Embassy of Senegal at number 47) correspond to some of the descriptions of 23 to 27 Horsecollar Yard in Flowers For The Judge.

“…the ancient firm of Barnabas and Company, publishers since 1810 at the Sign of The Golden Quiver…in the grand Queen Anne House in the cul-de-sac at the Holborn end of Jockey’s Fields which bore the sign of the Golden Quiver…” (pp. 7-8)

“After I and my colleague, Sergeant Pillow, had taken statements from the witnesses present on the premises at Number Twenty-three, Horsecollar Yard, I made a detailed search of the premises…In the room where the deceased was discovered I noticed a small ventilator…situated three feet from the ground and five and a half feet from the ceiling…My colleague and I then examined the lock of the door of the room and found that it had not been tampered with in any way. We then traced the outside wall of the building and discovered that the ventilator gave into a garage used by the directors of the firm.” (pp. 86-87)

“Mrs Rosemary Ethel Tripper…lived in the basement flat at Number Twenty-five, Horsecollar Yard, and…her occupation was assistant caretaker with her husband of the two blocks of offices, Numbers Twenty-five and Twenty-seven…‘I was referring to the car in the garage at Number Twenty-three,’ she said sharply, her refined accent temporarily deserting her. ‘Although we can’t hear the car in the daytime, of course, because of the traffic, any time after six o’clock the Crescent is so quiet you could hear a pin drop and of course you can hear the car start then, because the walls are so thin…’ ” (p. 91)

References to Vintage paperback edition of Flowers For The Judge, reissued 2015.

Turning into Bedford Row, house number 42 on the left (5) corresponds to Theo Bush’s house in Coroner’s Pidgin at 42 Bedbridge Row to which Albert Campion makes his way on foot from The Minoan restaurant on Frith Street -which we will visit later on the walk at location (15).

“The journey from the Minoan to Bedbridge Row in Holborn in a pitch-dark and taxi-less London proved to be more of an undertaking than the exile had expected, and it was nearly an hour later when at last he groped his way up the worn stone steps of the narrow Georgian house in the corner of the half-ruined cul-de-sac.” (p. 123)

Penguin paperback edition of Coroner’s Pidgin, published 1950, reprinted 1957.

Walk up Bedford Row. In Flowers For The Judge there is a cab-rank mentioned “at the end of Bedford Row”. This rank still exists today. Turn left into Theobalds Road. Look to your right as you do so to see the end of Jockey’s Fields (6) from which the lorry was seen to turn before it vanished in Coroner’s Pidgin

“This lorry went out of London during the second big [air]raid in September, nineteen forty…[carrying] the most valuable exhibits in the entire Museum [of Wine]; the Gyrth Chalice was there and the Arthurian Vase, priceless things, both of them, as well as a great deal more, and also by way of make-weight, I suppose, the two cases of [the Bishop of Devizes] Les Enfants. This lorry was last seen turning into Theobald’s Road while the raid was actually in progress.” (p. 117)

Penguin paperback edition of Coroner’s Pidgin, published 1950, reprinted 1957.

A few metres along Theobalds Road you pass on your left The Fryer’s Delight, an old fashioned fish and chip shop complete with formica-topped tables for those who wish to eat in rather than take away. The significance of this traditional “chippy” becomes apparent when you take the first turning on your left into Red Lion Street where, in Flowers For The Judge, there is a “fried fish shop” (7).

“Mrs Tripper flushed. ‘It was a shop in Red Lion Street – a fried fish shop, if you must know…I thought I might as well try some of their more expensive pieces. Some of these places are very high class, and the Red Lion shop is very nice indeed.’” (pp. 92-93)

Penguin paperback edition of Coroner’s Pidgin, published 1950, reprinted 1957.

Take the passageway, Lamb’s Conduit Passage, a few metres along Red Lion Street on the right (8). This corresponds to “the unsavoury Alley which is Red Lion Passage and [comes] out into the shabby comfort of the Square.” (p. 177 Vintage paperback edition of Flowers For The Judge, reissued 2015.)

At the end of the passageway, you enter Red Lion Square (9). This is where Ritchie Barnabas lives in Flowers For The Judge.

“Most of the flat houses had been converted into offices long ago. Standing back from the road, they turned blank eyes to the street lamps and only a single brightly-lit third-floor window twinkled at [Albert] mellowly through the budding plane trees in the dusty centre garden. He made for it and was rewarded. Ritchie was evidently a man of his word and was sitting up…It was a huge apartment with a very high ceiling, some two feet below which a shelf had been constructed round all four sides of the room.” (pp. 177-178)

Vintage paperback edition of Flowers For The Judge, reissued 2015.

Red Lion Square also corresponds to the description of Ebury Square in Look To The Lady which is said to be “just off Southampton Row” (p. 7 Penguin edition, 1950) (10) – the real Ebury Square is in Chelsea and is clearly not the square described in the novel.

Leave Red Lion Square along Old North Street and cross Theobalds Road at the crossing a few metres to your left. Continue in this direction to cross Southampton Row at the busy junction with Theobalds Road. Continue ahead past a large building (Victoria House) to reach Bloomsbury Square on your right. Turn right and walk up Bloomsbury Square then left at the far end to reach the corner of the square where you carry on in the same direction along Great Russell Street, passing the British Museum. Just beyond the British Museum, on the right-hand side, you will find 91 Great Russell Street (11) with the English Heritage Blue Plaque on the wall celebrating author George du Maurier. Apparently English Heritage turned down a request for a second plaque to be installed.

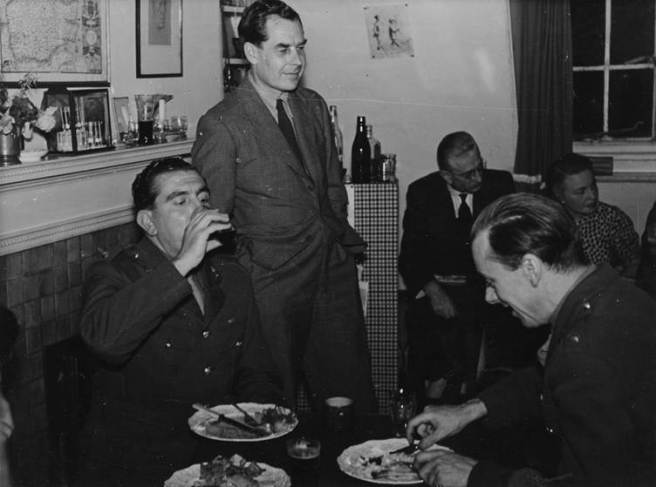

This building housed Doubleday’s London Office and was where Margery and Pip kept a flat from the 1940s to the 1960s. It served as Pip’s base in London while editing The Tatler. The Society archive has photographs of a party at the flat from the early part of their time there.

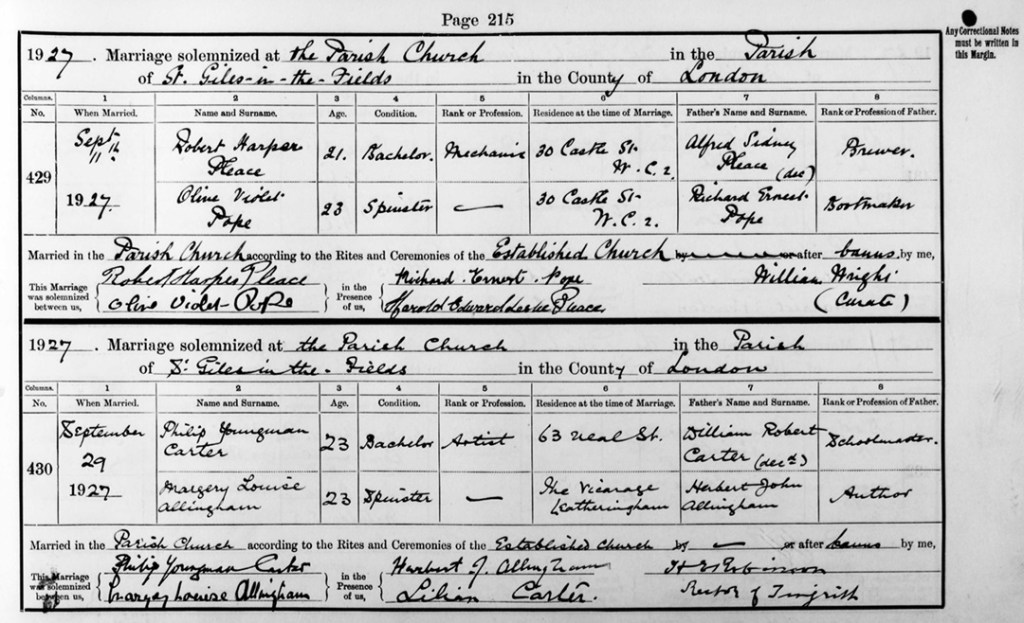

Continue to the end of Great Russell Street and turn left onto Bloomsbury Street. Cross New Oxford Street to join Shaftsbury Avenue and pass the Shaftsbury Theatre to reach High Holborn. If you divert briefly from the main walk and continue a little way down Shaftsbury Avenue you reach a junction on the left, Monmouth Street. A few metres along this side street there is a left turn into a smaller side street, Neal Street. Pip’s home before marrying Margery, referred to as “The Hovel”, was at number 63 Neal Street (12).

Return to the complex junction of Shaftsbury Avenue with High Holborn and turn left (if returning from the diversion to Neal Street) or right (if you have not taken that diversion) along High Holborn to reach St Giles in the Field Church on your left (13), where Margery and Pip were married in 1927. The church is open to the public Monday to Friday 8:15am to 5pm. Opening times at weekends depend on services and weddings or other functions. Below is the interior of the church (in case you can’t gain access).

From the church turn half left to walk along Denmark Street and cross Charing Cross Road to enter Manette Street. At the end of this cul de sac, you are able to walk through an archway under a building to reach Greek Street. As you do so, note the advertisement for Guinness painted on the wall – Dorothy L. Sayers devised slogans for Guinness during her work in advertising. Turn left here and then right into Bateman Street (14), which corresponds best of the various alternatives to the fictional Lord Scroop Street in The Fashion in Shrouds, site of the Hakapopulous restaurant. Bateman’s Buildings, on the right as you walk along the street, perhaps corresponds to the Augean Passage in the text.

“In summer-time the streets of Soho are divided into two main species, those which are warm and dirty and jolly, and those which are warm and dirty and morose. Lord Scroop Street, which connects Greek Street and Dean Street, belongs in the latter category. Number Ninety-one was a restaurant with high brick-red window-curtains and the name Hakapopulous in a large white arc on the glass. The main entrance, which was narrow and a thought greasy, had a particularly solid door with a picture of a grove of palm trees painted on the glass, while the back entrance, which gave on to Augean Passage, was, as the local divisional superintendent put it in a moment of insight, like turning over a stone.” (pp. 258-259)

J. M. Dent and Sons paperback edition published 1986.

Cross Frith Street, the location of the Minoan Restaurant (15), where “Stavros has the best food in London at the moment.” (p. 65 Coroner’s Pidgin, Penguin paperback published 1950, reprinted 1957), from which Campion made his late night journey to Theo Bush’s house, which we passed earlier (5).

Continue along Bateman Street to reach Dean Street. Turn left and then shortly right onto Meard Street which you follow to reach Wardour Street (16). Campion enquires of Lugg, in Flowers For The Judge (p. 62 Vintage paperback published 2006) “When you say ‘the club’, do you mean that pub in Wardour Street?…A wooden expression crept into Mr Lugg’s face. ‘No. I don’t go there any more. I took exception to some of the members. Very low type of person, they were.’”

Turn left along Wardour Street to reach Shaftesbury Avenue. Here turn right. There are several theatres on this stretch of Shaftesbury Avenue which might correspond to the Royal Alexandra Theatre mentioned in Coroner’s Pidgin (17) (p. 95 Penguin paperback published 1950, reprinted 1957) and the Sovereign Theatre mentioned in The Fashion In Shrouds (18) where Ferdy Paul maintained a flat “which a great actor manager had built for a charming leading lady on top of the Sovereign Theatre, [that] was, if sumptuous in the main, a trifle furtive about the entrance. The back of the theatre possessed a yard, now used by privileged persons as a car park, and in the yard beside the stage door was another, smaller and even meaner in appearance, giving on a flight of uninviting concrete stairs.” (p. 179 J. M. Dent and Sons paperback edition published 1986)

Cross Piccadilly Circus and walk along Piccadilly to reach a small alley on your right, Piccadilly Place, through which you reach Vine Street (19). This corresponds to the fictional Bottle Street, where Campion has his flat at number 17A above the police station. The real Vine Street police station was closed in 1997 and the building demolished. The fictional flat, readers may recall, could be accessed not only through the street door but through an ingenious back-entrance from a restaurant on Regent Street, the real-life modern-day equivalent of which you can find through the covered archway on your left as you face the blank end of the cul de sac.

“[Campion] made for a garage on the east side of Regent Street. ‘I hope you won’t mind,’ he said, beaming down at [Isopel] as they emerged into Picadilly Circus, ‘but I’m afraid I shall have to take you into my place by the tradesmen’s entrance. You never know at a time like this who may be watching the front door…It’s the one really safe place in London for you. There’s a police station downstairs…’ He piloted her across the road and down one of the small turnings on the opposite side, and paused at last before what looked to Isopel laike a small but expensive restaurant. They went in, and, passing through a line of tables, entered a smaller room leading off the main hall where favoured patrons were served. The place was deserted, and Mr Campion approached the service door and held it open for her.

‘I must show you my little kitchenette,’ he said. ‘It’s too bijou for anything.’

Isopel looked around her. On her right was an open doorway disclosing a vast kitchen beyond, on her left a narrow passage leading apparently to the manager’s office. Campion walked in.

A grey-haired foreigner rose to meet him…He led them silently into an inner room and threw open a cupboard doorway.

‘I’ll go first.’ Campion spoke softly. With a great show of secrecy the foreigner nodded, and, standing back, disclosed what appeared to be a very ordinary service lift which was apparently used principally for food. One of the shelves had been removed, and Mr Campion climbed into the opening with as much dignity as he could muster.

‘See Britain first,’ he said oracularly, and pressed the button so that, as if the words had been a command, he shot up suddenly out of sight…Within a minute the lift reappeared…The mysterious foreigner helped the girl into the lift…The journey was not so uncomfortable as it looked, and as she felt herself being drawn up into the darkness…she began to laugh.

‘That’s fine,’ said Campion, helping her out into the dining room of his flat.”

pp. 142–144, Mystery Mile. Vintage paperback edition published 2004.