The editor and anthologist Tony Medawar gave the following speech following the Society’s Annual General meeting in St Anne’s Church in Soho, London, on 15 June 2024

‘Few authors can have been as well served as Margery Allingham was by her literary executor, Joyce Allingham, and by her biographer, Julia Jones, the author of The Adventures of Margery Allingham – which I assume everyone here has read (Copies are available from Golden Duck publishing: https://golden-duck.co.uk/shop/the-adventures-of-margery-allingham).

This means that, while it was a very great honour to be asked to speak today, it also presented something of a challenge. What is there to say about Marge that hasn’t been said already? So, I thought about the date and what Marge might have been doing precisely one hundred years ago today, on the 15th of June 1924?

Well, Albert Campion was nowhere for a start. And while Marge knew Philip Youngman Carter, whom she had met at the Regent Street Polytechnic, they were not yet married nor even engaged, though in later years Pip Carter would claim that they had had a secret engagement.

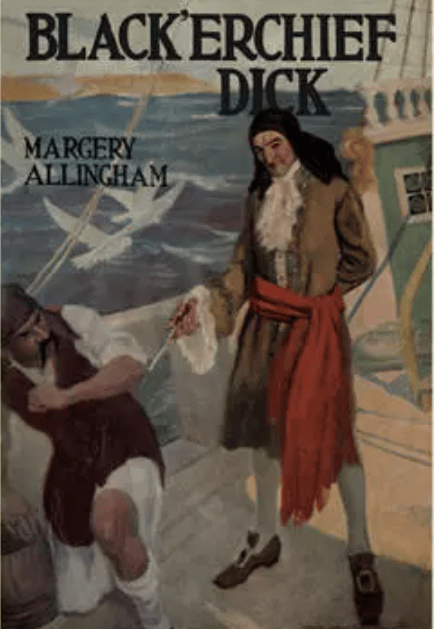

Perhaps the most important man in Marge’s life at this time was a pirate called Dick Delfazio, whom we all know as the eponymous hero of her first novel.

Blackkerchief Dick had been published in Britain in August 1923 and in America – under a slightly different title – a couple of months later, on the 5th of October.

In later years Marge would be very dismissive of Blackkerchief Dick but I rather like it and particularly the possibility that the plot was given to her by the ghost of a dead innkeeper.

Generally, and aside from stylistic criticisms, the novel received very positive reviews. In America, it was praised by one newspaper as the work of “an extraordinarily clever and unusual girl”; the newspaper – the Fort Worth Star-Telegram – went on to say that “one cannot imagine an American flapper (and Margery Allingham is at the flapper age) writing such a book as this. No, that is far too absurd. Modify it and say that one cannot imagine an American flapper reading this book.” In Britain, the Daily Chronicle’s reviewer was one of many whothought Blackkerchief Dick was “astonishing”.

Gatti’s Restaurant, The Strand, London

Julia Jones has told us that a few months after the book’s publication and even though Marge was only 19 years old, she was considered significant enough a writer to be invited to attend the dinner of the PEN Club at Gatti’s restaurant on the 5th of December 1923.

Marge was in good company as the guest list included GK Chesterton and HG Wells.

By April 1924, while she had not yet published another novel, Marge was also invited to attend the opening of the Sussex Room at Worthing Public Library. This time Marge turned them down … as did Hilaire Belloc, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Rudyard Kipling and AEW Mason – one can’t help thinking that the librarian invited anyone and everyone who had ever written a book.

So, back to my question, where was Marge on the 15th of June 1924?

The answer, probably, is in Flat 7, Hurlingham House in Blomfield Crescent in Bayswater, where she lived with her parents.

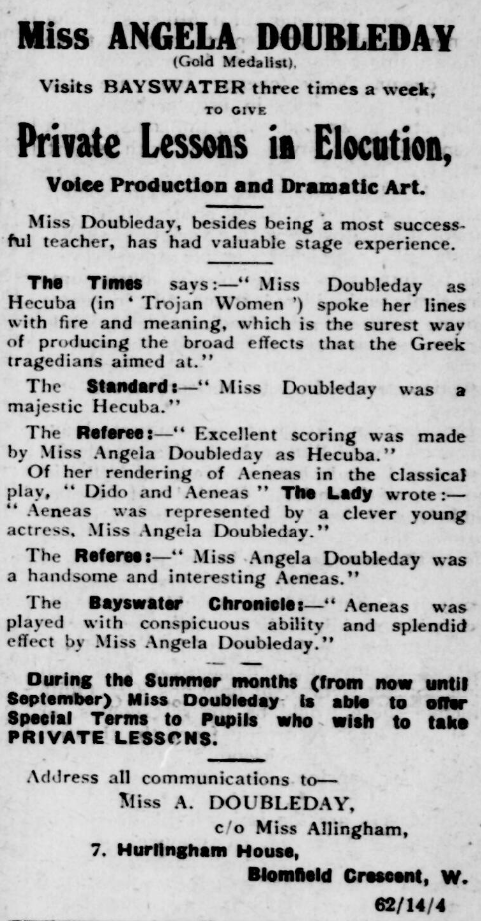

Marge also rented a studio in the gardens of Hurlingham House, and this was where, in March and April 1923, her friend Angela Doubleday gave “private lessons in elocution”, which as stated in newspaper advertisements had to be booked through Marge.

I am sure you will recall that Angela Doubleday played Aeneas to Marge’s Dido in her five act drama Dido and Aeneas and, as Julia Jones describes, the two girls were for a while “emotionally involved” with each other.

Paddington, Kensington & Bayswater Chronicle, 14 April 1923

So, I think – but don’t know – that that is where Marge was.

As to what Marge was doing, perhaps she was reflecting in the fact that Hodder & Stoughton had rejected her second novel, Green Corn, a novel about ‘bright young things’ which remains unpublished but, happily, is described in fascinating detail in Julia Jones’ biography.

Maybe she was working on a playlet called ‘Water in a Sieve’, for which her friend Donald Ford was writing the music.

Or Marge might have been adapting the plot of a film she had seen into a short story for one of her Aunt Maud’s film magazines.

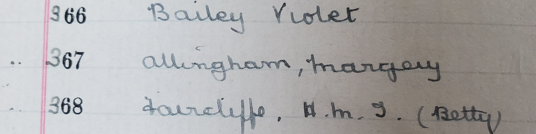

Or, perhaps, she was writing poetry. Certainly, one of her poems – ‘On the Portrait of a Pretty Lady, Painted 17__’ – would be published in the July 1924 issue of The Persean, a magazine published by the Perse School for Girls and with contributions by alumnae and staff as well as current pupils. Marge joined Perse Girls in January 1919, becoming pupil No. 367 as recorded in the school’s admissions register.

Entry in the register of the Perse School for Girls,

reproduced by kind permission of the Stephen Perse Foundation

However, she had left in July 1920, the same month that another piece by her had appeared in The Persean, a poem called ‘So Said the Blackbird’, which is reproduced in Julia’s biography.

In July 1923, The Persean carried a monologue by Marge entitled ‘Maid Marian’ in which Robin Hood’s true love mourned his death. This was one of a suite of dramatic monologues performed in January 1923 at Fyvie Hall, within the Polytechnic School of Speech, Training & Dramatic Art in Regent Street.

Under the overarching title Through the Windows of Legend, the monologues were recited in costumes, which – as you might have anticipated – Marge also designed, making them with the other students; and the music, incidentally, was composed by Donald Ford.

According to Julia Jones, there were 16 monologues in the series. As well as ‘Maid Marian’, the archive includes ‘The Lovers’ Walk’ and ‘Amy Robsart’, a monologue about the Elizabethan woman whose mysterious death has confounded historians.

Another, ‘The Ballad of Rowenne’, was about a knight and his lady.

And there was one about a witch, called ‘Tib Merriweather’.

Marge herself had recited one about a highwayman, ‘Jerry Abbershaw’s Sweetheart’ and The Bayswater Chronicle gave her an ecstatic review – “Margery Allingham was decidedly at her best – if indeed there can be any ‘best’ in regard to her marvellous acting.

For she acted the part to the life, and her vehement protests, her passionate entreaties, her bitter anguish, as she is forced to see her lover die, seemed to come so naturally to her that the character was made ‘real’ to the audience. One could vision the surging crowds, the onward press of the people, eager to obtain a glimpse of her lover’s execution. It was a splendid performance and it was to be regretted that Miss Allingham had not elected to appear a second time in the programme”.

Five of Marge’s monologues appear not to have survived: ‘The Sea Fairy’; ‘The Watch’; and three comic pieces: ‘The Player’s Boy’, ‘The Double Life of Elspeth ‘Iggs’ about a girl who wants to be a film star and ‘Miss Pringle Has Her Little Say’ about the keeper of a lodging-house, possibly not unlike Sarum House where Marge lodged while studying at Perse Girls.

You will recall that Marge had joined the Perse in January 1919, and it was in March 1919 that she first had a poem published in The Persean.

It was called ‘A Vision’ and when it was published Marge was still only 14 years old.

While it is the first time a poem of hers was published, it was not the first time that she had appeared in print – that was on the 14th of April 1917 when her short story ‘The Rescue of the Rain Clouds’ was published in Mother and Home, a magazine edited by her Aunt Maud.

Now, the poem ‘A Vision’ isn’t mentioned in Julia Jones’ wonderful biography and there doesn’t appear to be a copy in the archive at Essex University.

So while I didn’t manage to find out what Marge was doing on the 15th of June 1924, or where she was, I did manage to find one of her earliest publications which I believe has never previously been recorded, a piece that I’m sure The Guardian would describe as “a literary curiosity among her juvenilia”, which is how, in 1923, their reviewer suggested Blackkerchief Dick might best be considered.

Tony concluded by reading Marge’s short poem, which is reproduced below by kind permission of The Stephen Perse Foundation.

A VISION.

The sun all gold and crimson, like a princely monarch’s gown,

Sank slowly over yon hill, and hallowed with a crown

Its murk and all o’ershadowing peak

E’en as I watched the shades of night silently crept around,

And I saw the hill with its crown of light in deep black darkness drowned;

And there on the topmost summit a figure in glistening white,

An emblem of peace and joy, of purity and light,

His head bent low, his wings unfurled,

Both hands outstretched to bless the world.

M. ALLINGHAM,

Middle IV.